Despite a late start time, Kris Klessig tapped into the mental and physical toughness she needed to cross the New York City Marathon finish line.

Most runners know the New York City Marathon by reputation: It’s the largest marathon in the world. Even in a pandemic year with the number of participants capped at around 30,000 compared to the normal nearly 60,000, that comes with the most excited runners, the most crowded streets (on the course and on the sidewalks), the loudest spectators, and the most palpable energy from Brooklyn to the Bronx.

But for back-of-pack runners, that experience can be a little different. “I was in the fifth and final wave, and didn’t start running until after 12 noon,” says Kris Klessig, 49, from Santa Fe, New Mexico. “By the time I came over the Queensborough Bridge into Manhattan [around mile 16], it was dark, and the crowd was down to stragglers.”

Instead of the “wall of sound” that hypes runners up on First Avenue after the bridge, Klessig heard a different noise somewhere between miles 17 and 18: a megaphone announcing the official end of the marathon’s police escort. “At first, I panicked,” she says. After all, one of her fears coming into the race was the idea that she would be in the last corral of the last wave, one of the slowest runners on the course.

But part of her marathon training with Tonal this cycle was working on her mental strength and shifting negative mindsets. “I thought, I’m okay. I know I have enough time to finish. I’m going to turn this into a positive,” she says. “I’ve got a police escort! Look how important I am! And that was really cool because it helped me dig a little deeper than I thought I could.”

With that change in perspective, Klessig, who used a walk/run strategy in this race as well as in nearly 50 half marathons (she’s working on completing one in every state), was able to slip back into a run. “I started passing people at that point,” she says—a point she had been nervous about in training since she hadn’t run more than 13 miles in a long time. “When I did pass someone, I would high-five them or fist-bump them and say ‘Power share!’ or “Power up!’ I tried to give them a little bit of that power I found, and that, in turn, made me feel more energized and powerful.”

Mental strength, just like physical strength, takes training. And one of the easiest ways to do that is through meditation, which can help you stay in the moment and keep from panicking, just like Klessig did. “I did a lot of breathwork meditations with Coach Jake on Tonal, just trying to increase the depth of my breathing and my lung capacity at rest and hoping that translated into something for the race,” she says. This practice certainly helped her go into the race feeling calm and relaxed—a place from which you can make smart racing decisions. “Everyone talks about the taper crazies, and I felt fine. I wasn’t stressed at all,” she says.

Of course, you can’t run or walk 26.2 miles without physical strength as well. Throughout her marathon training, Klessig supplemented her running with Tonal’s 5K Strong program, which trains important muscles for powering your gait and improving core stability. As someone who knows she doesn’t always recruit her glutes—the muscles that literally propel you forward while running—that was a major priority for Klessig.

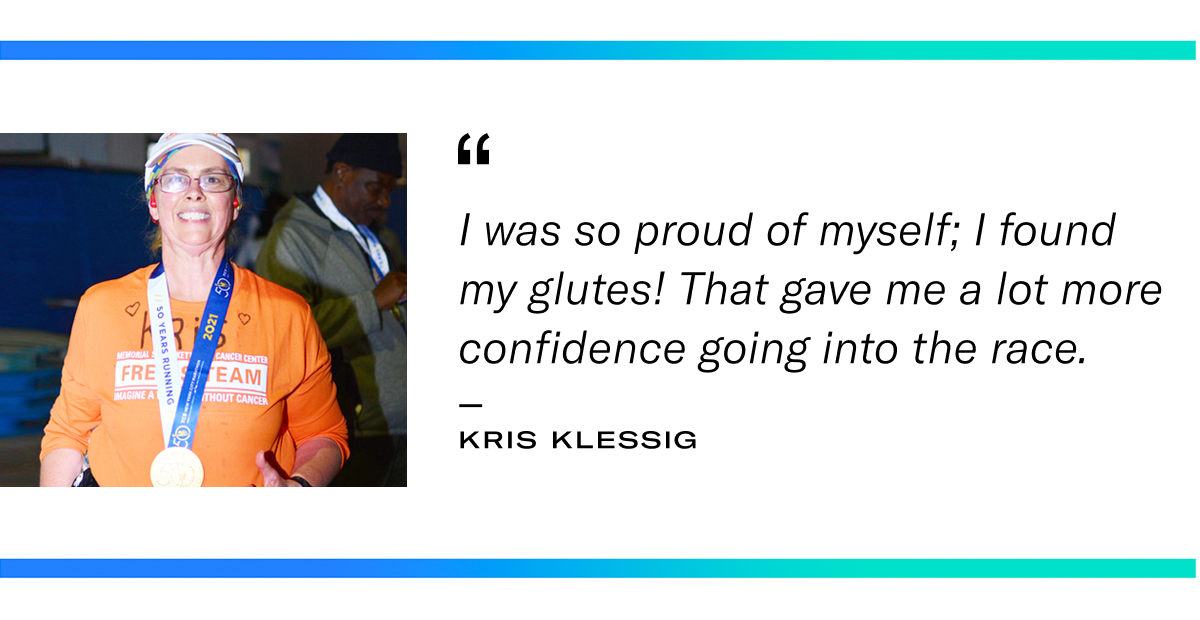

“There’s this move where you sit with your legs bent in a Z-shape and then try to lift your hips off the ground without using your hands,” she says. “During the first three weeks of the program, I had to push with my hands. But in the last week, right before the race, I was able to get up without using my hands! And I was so proud of myself; I found my glutes! That gave me a lot more confidence going into the race.”

Klessig’s focus on core work also showed up on race day. “I noticed that I get lower back pain at the end of and after my half marathons because I slouch forward as I get tired,” she says. “But during training, my core Strength Score on Tonal went up significantly. In my race photos, I was definitely standing up straighter, even at the end.” After the marathon, her back didn’t hurt at all. “That’s a huge change that’s never happened to me before,” she says.

With those two outcomes, Klessig’s only pre-race regret was that she didn’t start strength training sooner. Running is already a sport of muscular endurance, but focusing on muscle building can help unlock new levels of strength during hard moments in the marathon. And that’s a lesson Klessig says she’ll take to her upcoming races—she’s got the rest of her 50 half marathons to finish before her 50th birthday next year.